What the projects tell us about communities

1. Feeling a sense of belonging to an area is complex – but it can be nurtured

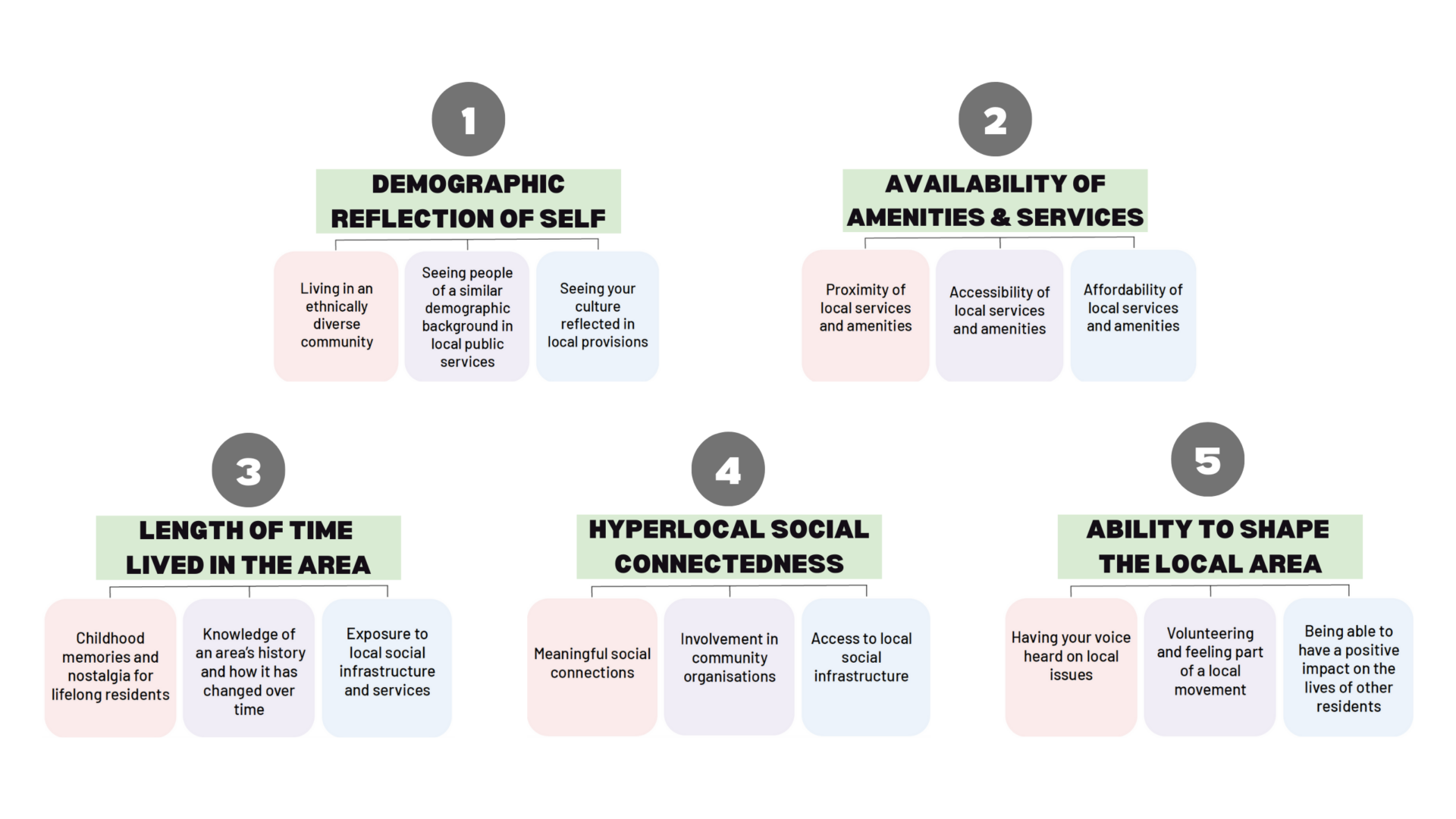

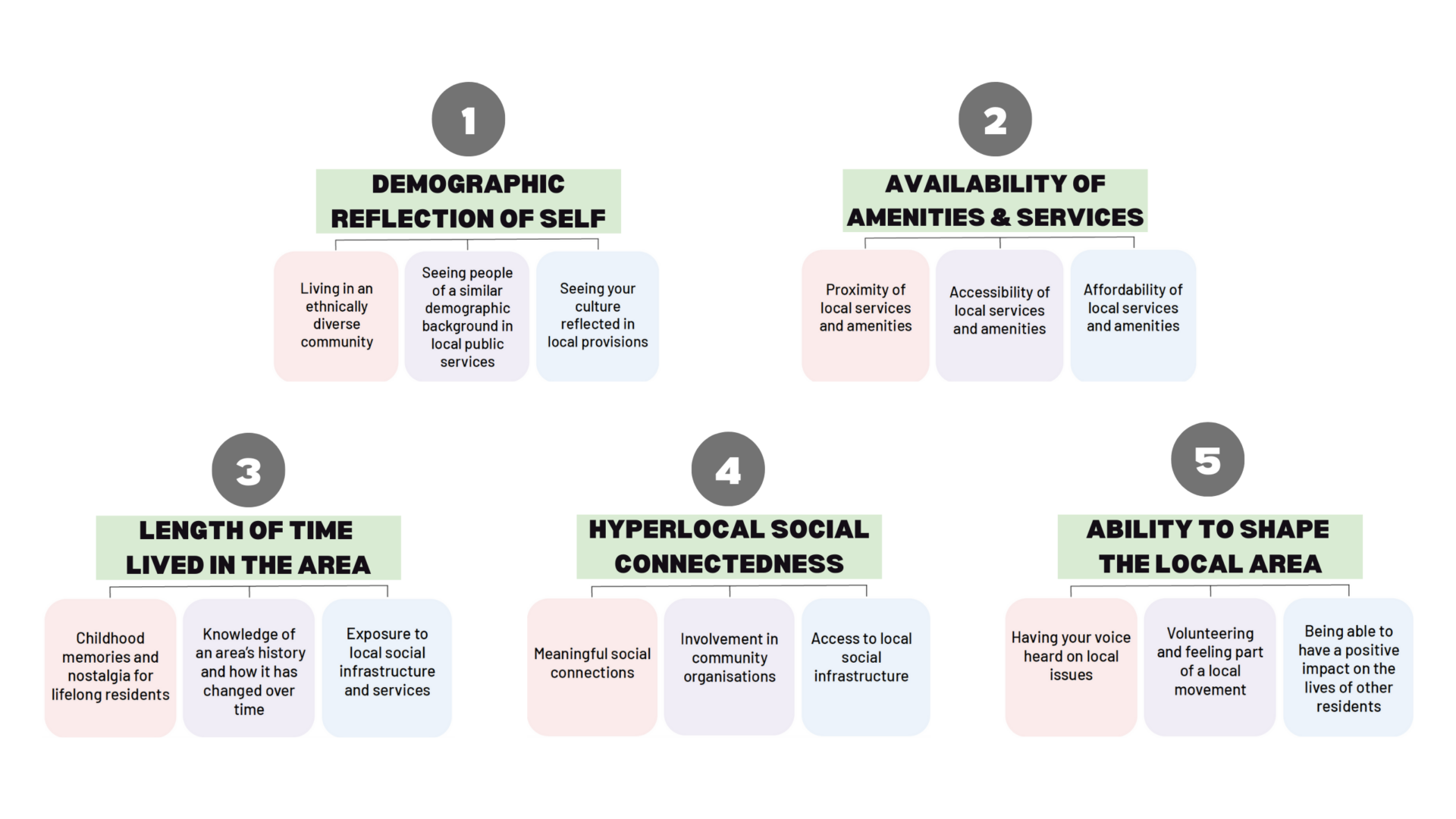

In their project Making Sense of Belonging, Neighbourly Lab engaged Londoners to help unpack the different ways people feel that they ‘belong’ to a local area. Their work, which included ethnographic deep listening with residents in Lewisham and Newham, uncovered how people felt they belonged somewhere.

Predictors of local area belonging (1 = strongest)

Neighbourly Lab used these models as the basis for their own index, and their scores will feed into the ‘local area belonging’ indicator for the latest update of the London Civic Strength Tool.

2. Representation can have an important impact on people’s lives if Londoners feel that their voice is being heard

In their report on the initial version of the London Civic Strength Tool, the Young Foundation called for more data on representation of elected officials by age, gender and ethnicity. This would help better understand how well Londoners feel able to interact with institutions and be represented by them.

Migrant Democracy Project’s work on the first-ever fully representative survey of elected councillors in London responded to this challenge. Their analysis shows that young people, women, Londoners from minoritised ethnicities, people that haven’t undertaken higher education, people that live with disabilities, migrants, and people that identify as Christian, Muslim or Hindu are underrepresented within London councils.

3. Inequalities persist in access to community sport and physical activity

London Sport used funding from the Civic Data Innovation Challenge to get a deeper understanding of London’s community sport and physical activity (CSPA) offer.

Alongside 107 partner organisations – including local authorities and sport national governing bodies – they mapped activities and created a pioneering new open data standard. Because the data each organisation held varied significantly in both quality and format, they tailored engagement to ‘the needs and capabilities of each organisation and data holder’, with communications focused on the value of signing onto the club data standard.

The result was a staggering 6,891 CSPA entries added to the sports club database, and more granular information about where gaps in provision across London were found. Importantly, London Sport found a correlation between high social and economic deprivation in local areas and fewer clubs – showing the need to grow grassroots sports and exercise in neighbourhoods that experience the highest health inequalities.

4. There are ways to make civil society data more transparent and accessible

Early versions of the London Civic Strength Tool drew on uncleaned Charity Commission and 360Giving data to estimate the contribution that the charity sector makes to social support, community action and financial resources within places.

The project led by MyCake was built on the recognition that organisations do not necessarily contribute to local civic strength simply because they have offices in that place.

Working with Superhighways, they developed a new method to assess which organisations were most likely to contribute to London’s civic strength. Through interviews with charity professionals and policymakers, they created a working definition of ‘local’ organisations and identified which London-based groups to exclude, such as those listed in the Charity Register but focused on national or international efforts. Exclusion criteria were used to clean Charity Commission data, which was then linked to 360Giving data to estimate the value of local grant making, among other measures.