As Portfolio Manager at the Charity, I see the growing body of evidence linking poor health with the built environment around us. Over the last few decades, the number of fast food outlets in our South London boroughs has increased exponentially, and streets have not been designed with pedestrians in mind. For too long the unhealthy option has been the easiest.

As part of our children’s health and food programme we’re exploring solutions that make the healthier option the default. We want every child to be able to run, play and access healthy food regardless of where they grow up.

We’ve partnered with Gehl, an international urban design practice. Together we will explore local foodscapes – the intersection of food places, public life and public space. The focus has been on the urban streets of Southwark, where up to one in three year six children are obese.

One of the key take-aways for me has been how perfectly some elements, such as fast food outlets, are designed to attract young people. It made me realise how difficult it is for healthier options to compete for young people’s time and attention. The findings show that we need to work with these organisations to make it easier for young people to be healthy.

Hear more from Sophia below about how the built environment is shaping young people’s daily food experiences.

Exploring Southwark through young people’s eyes

At Gehl we use a people-first design process to understand how public spaces in cities cater for public life. People’s experiences allow us to identify challenges and develop strategies, and designs to improve quality of life.

Our investigation into young people’s food habits took place in two South London neighbourhoods, Camberwell Green and Peckham Rye. The aim has been to identify urban design interventions to address childhood obesity. Camberwell and Peckham are close in distance and have similar demographics but their childhood excess weight rates are different. Camberwell Green has one of the highest rates of childhood obesity in the UK at 52% while Peckham Rye has a rate of 32%.

In June 2019, we collaborated with 16 local community researchers from The Social Innovation Partnership and 34 public life surveyors hired from Kaizen Partnership to conduct a Foodscape Survey.

What is a Foodscape Survey?

In Southwark’s Foodscape Survey our surveyors tracked public life behaviour and the quality of the public realm. This survey asked how people use their urban environments, how they socialise, and the activities they engage in. We also observed how food places play a role in determining food habits among various demographic groups. The community researchers also conducted over 400 qualitative interviews with adults and young people aged 6 – 16.

With the community researchers, we led a participatory engagement process with 22 local 12 – 16-year-olds. We used a model that involved walking tours led by them and workshops to create their own ‘daily route’ maps and visions for their ideal healthy neighbourhood. This approach gives participants the chance to show us first-hand what they experience in their daily lives. It also acts as a demystifying agent in myth busting our own assumptions about what they enjoy or not.

Experiencing the neighbourhoods from their perspective and learning more about the challenges they face was enlightening. By giving young people a space to share their experiences, some universal truths were uncovered about their behaviour and basic needs. Most significantly, that many problems with the food system are about so much more than food. Data from the Foodscape Survey was paired with the input from workshops with local young people and stakeholders, such as Southwark Council members and Transport for London (TFL) staff. This helped us develop initiatives to inform future strategic decisions on the impact of poor food options and limited civic spaces on young people.

Community researchers interviewing local young people in Camberwell Green on their daily eating habits

Here is what we found

The life and character of the street defines people’s foodscape experience

- During both weekends and weekdays people spent far more time on the street than in parks and squares, making the high street the backbone of these neighbourhoods. Young people weren’t observed spending much time in the public realm but were mostly present in fast food places during and after school hours.

- Fast food places have a systematic method of marketing and communication that creates a gravitational pull on young people. The signals they send indicate the availability of inexpensive food at all hours of the day.

Identifying signals in the environment that affect how and what we consume, taken from Food Systems & Public Life report

Transit hubs are hot spots for eating food with friends

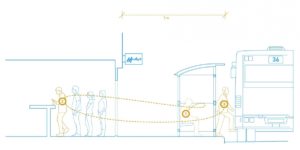

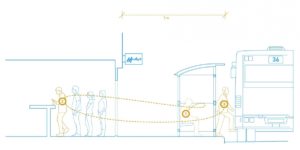

- When young students commute to and from school, their exposure to fast food intensifies. After school, unhealthy food is omnipresent on the high street and at bus stops where young people are free to eat what they like. Across London, fast food outlets are strategically positioned to follow public transport and commuting routes. In fact, 25% of all people observed in the Foodscape Survey were waiting for public transportation. The most dominant activity that young people were engaged in was waiting for transportation and socialising while doing so.

Fast food places acting as waiting places next to transport hubs, taken from Food Systems & Public Life report

Food places are acting as civic beacons

- Cuts to local authority budgets have limited access to civic and cultural amenities. As a result, it appears that young people are replacing civic amenities, such as youth or sports clubs, with fast food outlets. These fast food outlets are desirable places to spend time. They are low-cost, have informal seating, often provide free Wi-Fi, and large groups can spend a long time there. In fact, the interior configuration of fast food places is similar to a well-functioning public space. They allow for a range of activities and users. Different social dynamics can exist in the same place, it is accessible by different modes of transport, and there are relaxed social norms.

After school is the busiest time of day when fast food outlets become packed with people. These are some of the few places that young people can socialise that are both affordable and not strictly monitored. When asked, young people said they eat out primarily because they like the food and because they want somewhere to spend time with their friends.

Healthy eating options are nearly impossible to find along high streets where youth commute every day

Recommendations for the future

After spending time with local young people, we learned that they don’t always feel safe in their neighbourhoods and find that fast food places offer both safety and shelter. We have learned that for young people, unhealthy food may be a symptom of a larger problem. Therefore, in addition to the urgency of providing safe and welcoming places that serve fresh and healthy affordable food, the public realm must better serve people’s basic needs.

We recommended the following improvements

- Strengthen public space networks by connecting existing amenities through a youth friendly walking and cycling network. Improved streets would make it possible to move through their neighbourhoods safely while lessening exposure to fast food on the high street.

- Transform some of the ward’s transit stops with invitations to have a unique experience while waiting. Transit stops are an extension of fast food places. Interventions must offer a new experience closer to schools, creating the possibility for change in students’ daily habits.

- Create new civic spaces for young people that are safe and social spaces. By offering entrepreneurship opportunities, social experiences and education around food, civic spaces would become catalysts for a new kind of life in the neighbourhood.