Daliya’s story

Daliya is a 27-year-old mother with multiple long-term health conditions living in South London. Her income fluctuated from month to month and her financial struggles had a huge impact on her mental health.

Financial foundations for adult health

Dreaming of a better place

People living on low incomes have more complex finances than most people: their day-to-day incomings and outgoings are less predictable, they have higher risks to income and use a wider variety of finance services.

In addition, they often experience sudden changes in approach and benefits schedules from creditors, welfare and social care providers. If their housing conditions are unstable, mental health can rapidly decline.

Add the complexity of managing one or more long-term conditions, and their bandwidth to withstand cliff-edge moments becomes very limited.

Andrea is a 44-year-old single woman originally from Latin America with no dependents. She moved to the UK in early 2018 in hopes of finding a job and becoming financially stable.

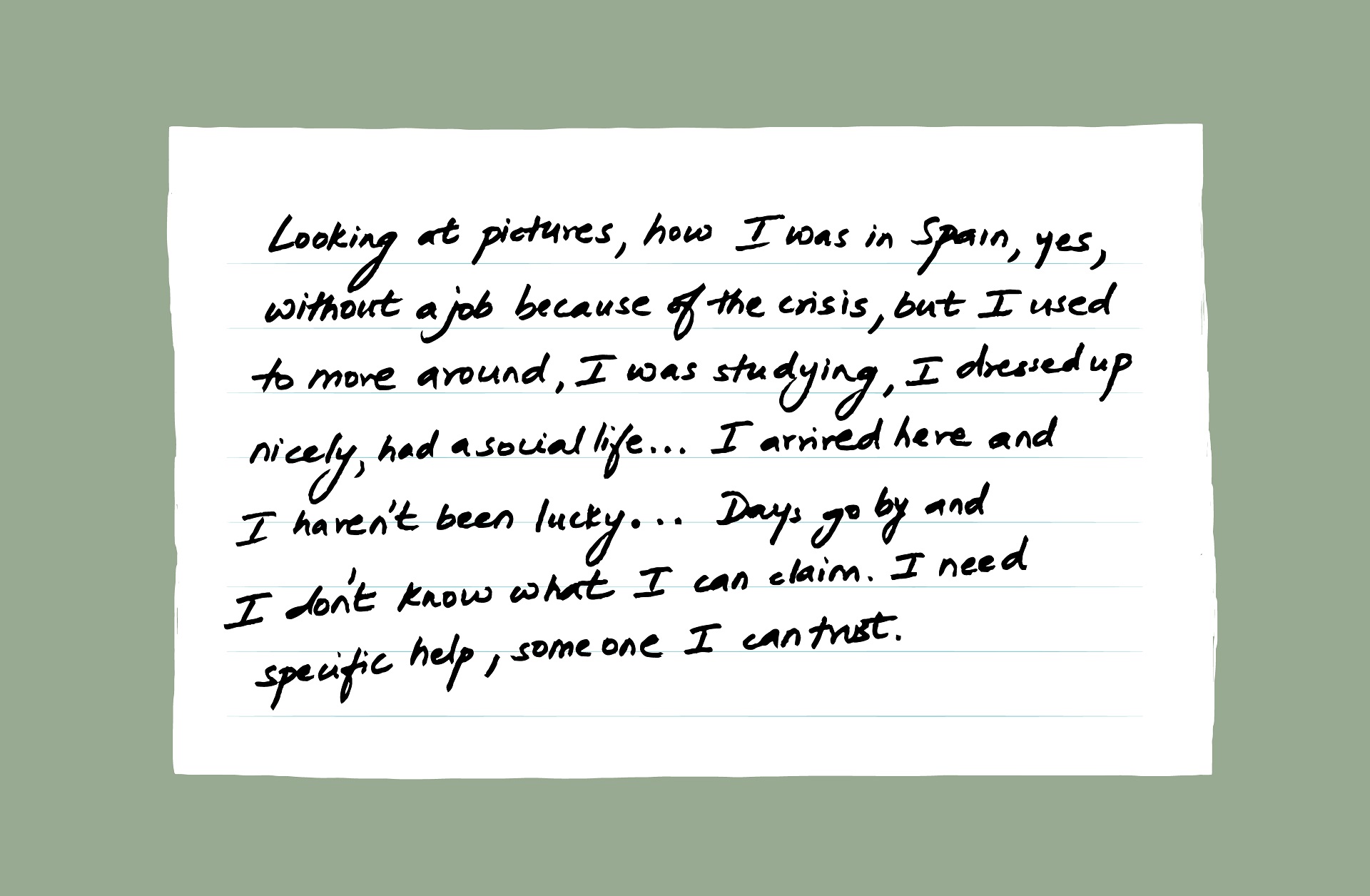

Before arriving in the UK, Andrea lived in Spain, where she was registered as disabled due to multiple long-term health conditions including asthma, arthritis, epilepsy, anxiety and depression.

She decided not to transfer her disability status from Spain to the UK because she wanted to find part-time work once she moved. After arriving in London, Andrea got a job working part-time for a cleaning company servicing the healthcare sector, one of the biggest employers of the area.

Andrea was drawn to South London, which has attracted a large wave of Spanish and Portuguese-speaking immigrants. Being new to the UK and in part-time employment, Andrea managed to find her first accommodation in the area through a sub-let.

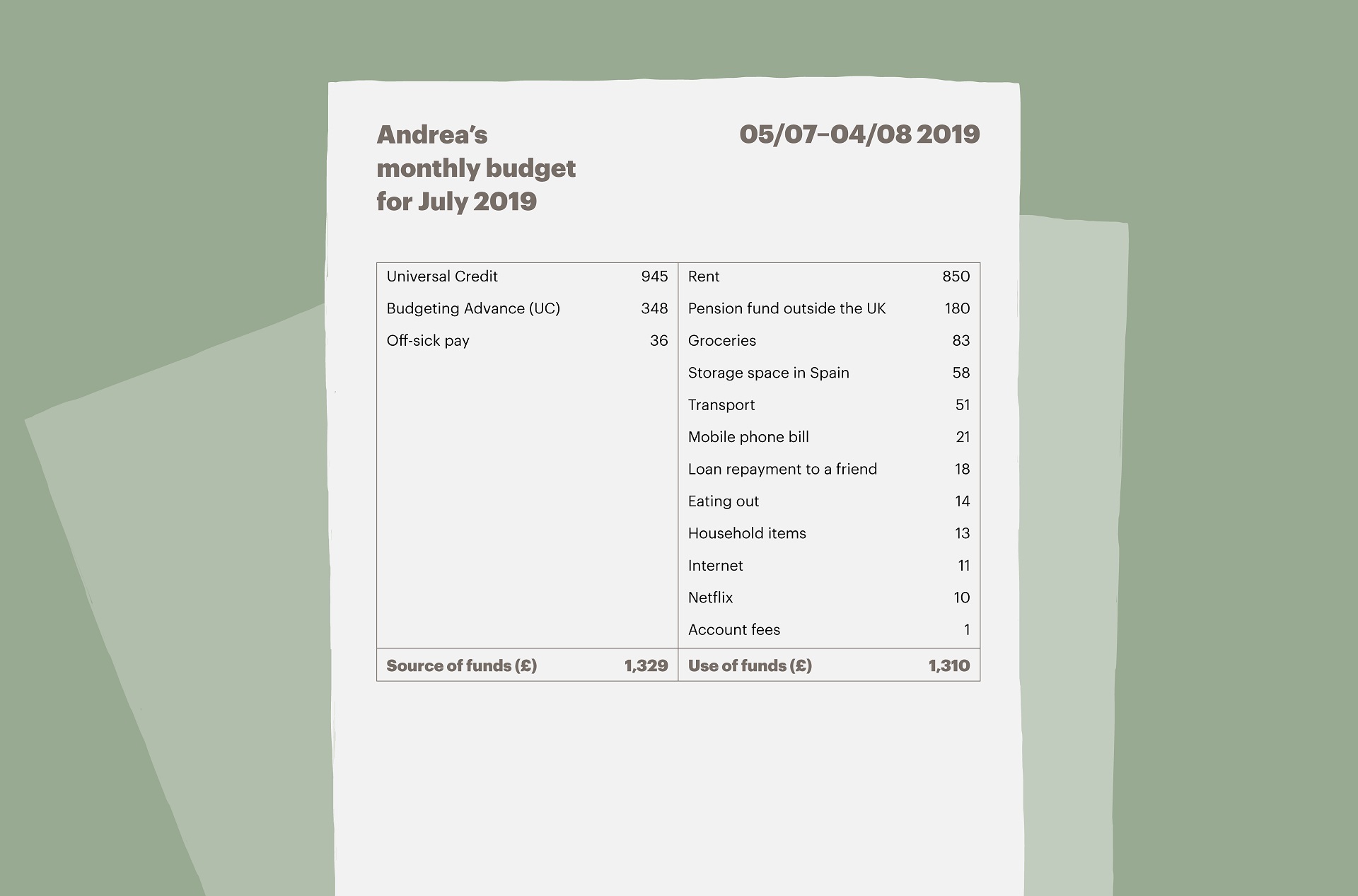

When we first met Andrea, she was living in single room in a shared flat, for which she was paying £850 a month. She used to pay for rent through Universal Credit, which she accessed because she had been off-sick since April 2018, when she injured herself at work while cleaning pools at a hospital.

Even though she was glad for the financial assistance, her housing conditions were extremely bad, and they made her feel sick. Her room and house were humid, constantly flooding and had mould growing on the walls and in the carpet.

Unsurprisingly, this made Andrea’s asthma worse and led to severe asthma attacks at night. Talking to Andrea and others revealed that precarious employment and lack of good quality, affordable housing, are key reasons for the ill health of low-income communities.

In addition, unstable housing causes major negative impacts specifically on mental health because of the stress that moving, and the constant worry about affording rent or managing living conditions, produces.

Andrea’s poor living conditions made her already precarious health decline and led to her needing medication to cope with her asthma attacks.

Even though she spoke to her landlord about the strain the mould and constant flooding put on her health, the landlord refused to do anything to mitigate the issues. When her worsening asthma became too much, Andrea sought help from her local council, who advised her that she was eligible to access social housing.

Andrea took the necessary steps to apply for social housing but was informed in July 2019 that no social houses were available at the time. As she waited for a housing placement, Andrea had to continue paying rent for her current flat.

This put an immense strain not only on Andrea’s health, but also her finances, because the price charged by her landlord was almost equivalent to her benefit payments. Because Andrea’s living expenses included more than just rent, she sought out creditors and asked for a Universal Credit budgeting advance to pay for her outputs.

In August 2019, Andrea was still waiting to be re-housed. This time, the council made a formal assessment of her accommodation. Upon investigating, they advised her to stop paying rent because the house was in such bad condition.

Andrea followed the council’s advice and was able to save some money by not paying for a month of rent, which had a positive impact on her anxiety, depression and finances because of the stress it relieved.

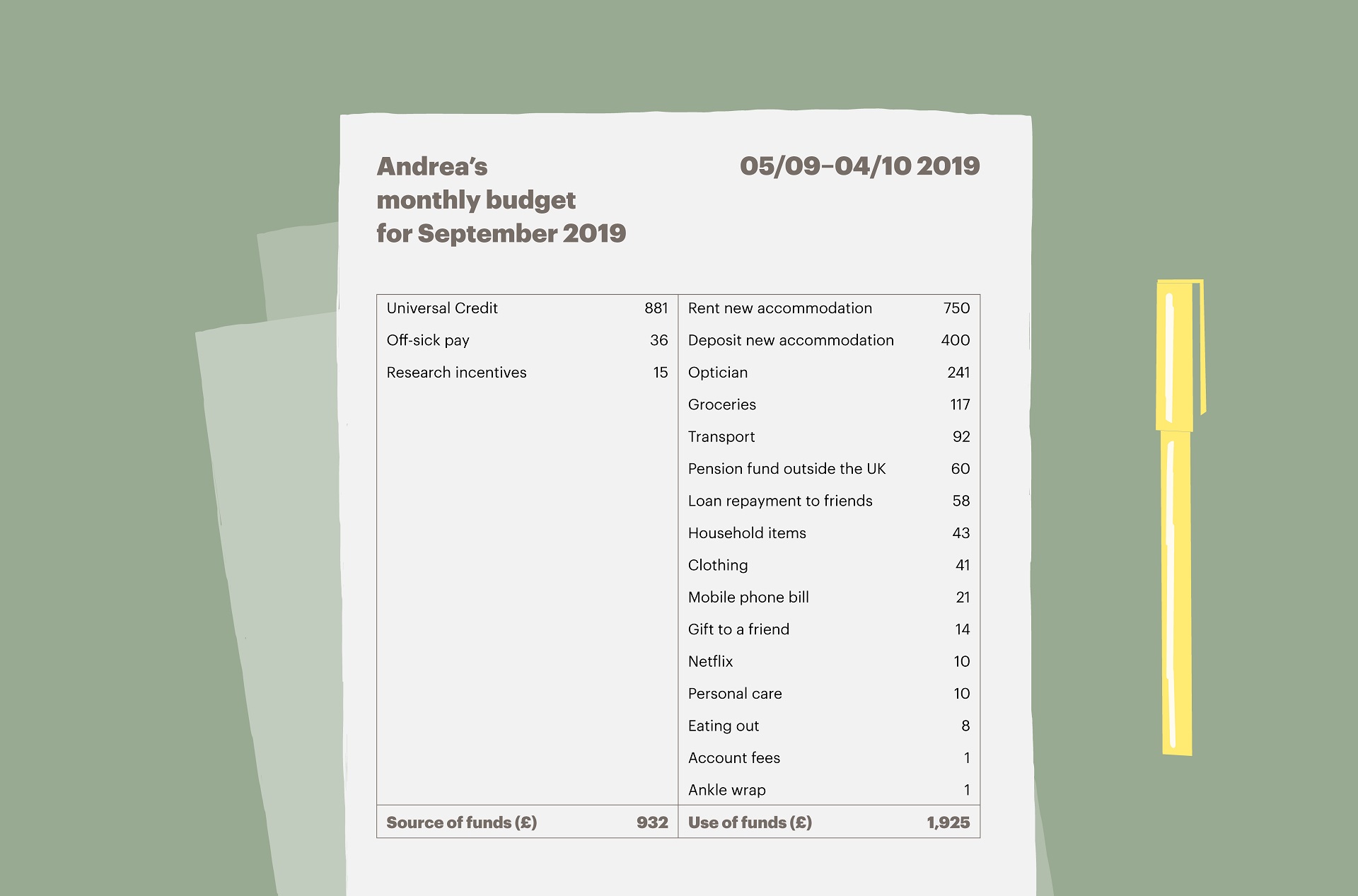

This allowed her to look for and find a new private accommodation in September 2019 and pay for the deposit and the first month of rent. Unfortunately, the money that Andrea was able to save in August by skipping a rent payment was not enough to cover all of her September expenses (see table).

In the following months, Andrea had to ask several family members and friends for loans totalling £1830. On top of this, Andrea’s Universal Credit was impacted by the scheduled repayments for the budgeting advance she asked for in July 2019. And, she still had to pay for private rent because the council had not yet found a social housing placement for her.

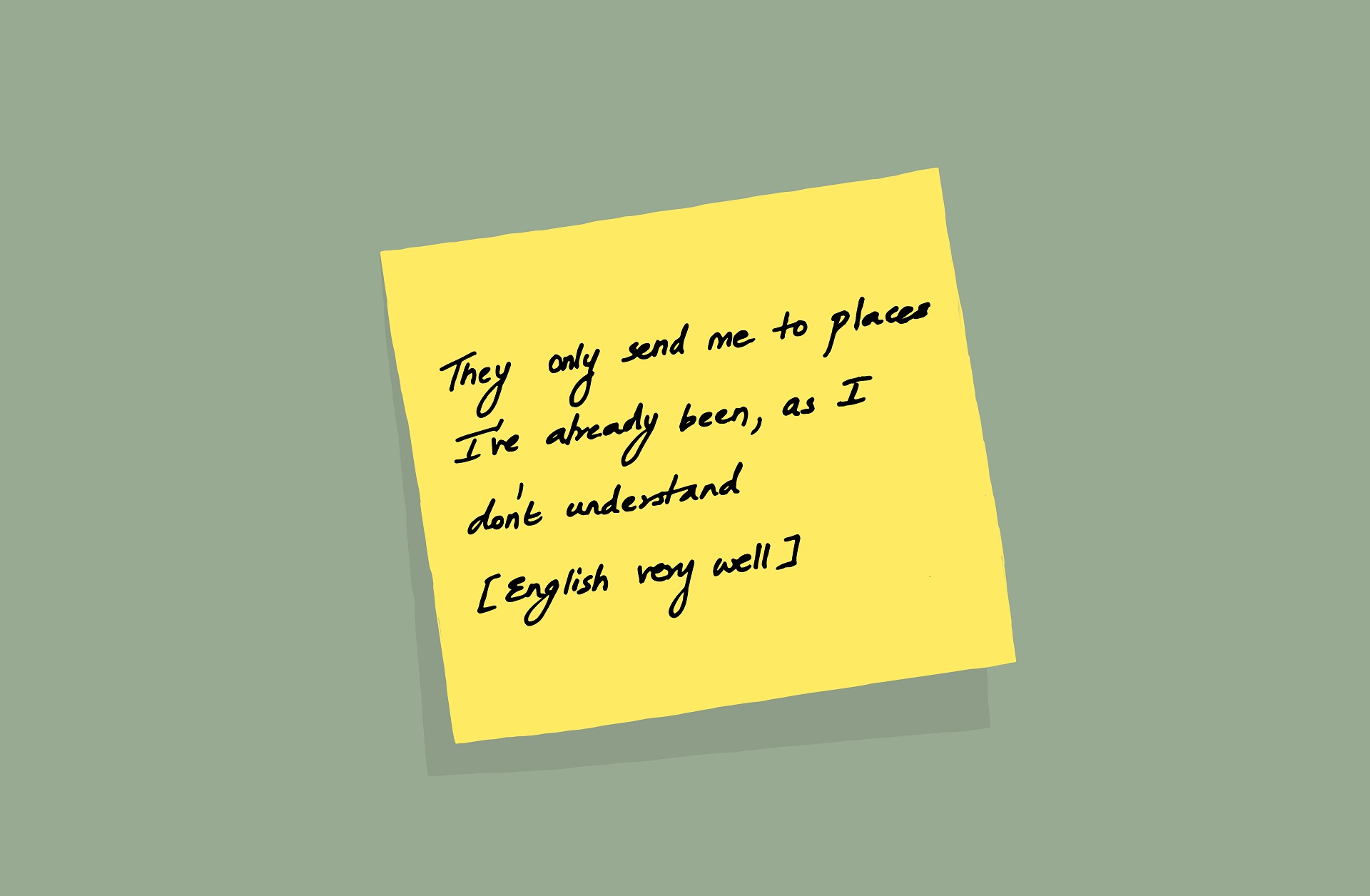

Every day, Andrea juggled multiple sources of income and credit that varied from month to month. After a while, Andrea began feeling unsupported by the council, who made little effort to cross language barriers and sent her to visit the same houses multiple times, each time concluding that she was not eligible for those particular houses.

Andrea found the situation very frustrating, overwhelming and financially difficult, which exacerbated her health conditions.

While talking to Andrea in December 2019, she made it clear that she needed supplementary support to cope with her situation because her health was compromised by the stress and lack of support with her housing case.

Andrea expressed how searching for a council house was a particularly challenging activity for her. This was because she already experienced a hectic life full of health issues, health check appointments, re-assessment of working capacity and benefits and debt repayments.

Her former landlord’s lack of concern for the poor living conditions in her house, the council’s delay in getting Andrea social housing and the pressure she felt to pay back her creditors for the money she had borrowed all contributed to Andrea’s growing anxiety and worsening mental health.

Andrea knew she needed more money but felt stuck because her employer had not yet deemed her fit to work again. On that occasion, she said she was having second thoughts about asking for disability status in the UK.

Had her employer and other creditors, including her landlord, the housing council department and lenders, adopted Financial Conduct Authority guidance on treating vulnerable customers fairly, Andrea could have been more confident that she was getting fair access and quality of services and more willing to engage with her creditors.

We met Andrea for the last time just as the COVID-19 pandemic was beginning to surface in Europe. She was still waiting for her social housing situation to be fully solved. When we last spoke with her in February 2019, she was living in shared accommodation with 13 other people – a living situation that made it difficult to follow social distancing guidelines.

Since vulnerable people with underlying health conditions are far more susceptible to the virus, Andrea, having asthma and living in cramped housing, was not in a good position to withstand the imminent impacts and ensuing economic downturn the pandemic would bring.

Andrea’s experience was sadly not unique, but there are steps organisations can take to protect the health of people like her:

Financial foundations for adult health

Daliya is a 27-year-old mother with multiple long-term health conditions living in South London. Her income fluctuated from month to month and her financial struggles had a huge impact on her mental health.

Financial foundations for adult health

Luisa is a 28-year-old mother of two young children, aged one and four. She lives with depression and anxiety. When Luisa's finances caused her depression to worsen, this manifested itself through physical symptoms.

Financial foundations for adult health

Shannon is a 55-year-old single mother with four teenagers. Her precarious working conditions negatively impacted her health, especially when she couldn’t take paid time off work when she needed it.